Imagine whispering secrets in plain sight while enemy soldiers stand close enough to hear every word. That’s exactly what islanders on Jersey did during World War Two, using their ancient native tongue, Jèrriais, as a living codebook the Nazis couldn’t crack. It wasn’t a cipher machine, it wasn’t high technology, just ordinary people speaking a language so unique and unfamiliar that it baffled their occupiers. And today, that same “secret weapon” is making an unlikely comeback.

A Viking Legacy in the English Channel

Jersey, the largest of the Channel Islands, sits just over 20 kilometres from the French coast, yet it isn’t French at all. A British Crown Dependency, Jersey has long been a cultural crossroads. Its native language, Jèrriais, is a descendant of Norman French, flavoured with traces of Old Norse from Viking settlers centuries ago.

For hundreds of years, it was the islanders’ everyday speech, complete with different accents and even unique words depending on which parish you lived in. On an island barely nine miles long, that’s a patchwork of dialects rich enough to stump even locals if they strayed too far from home.

Outsmarting the Occupiers

In June 1940, German troops marched onto Jersey, making it the only British territory occupied during the war. With no chance of military resistance, locals fought back with subtler weapons: humour, defiance, and language. Jèrriais, unintelligible to outsiders, became the island’s clandestine code.

Even French-speaking Germans struggled to follow the rapid-fire exchanges of the Islanders. Messages, jokes, and resistance plans slipped under the occupiers’ noses, woven seamlessly into daily life. “Articles openly printed that it’s best to speak Jèrriais so ‘certain people’ won’t be able to understand it, i.e., the Germans,” explained linguist Geraint Jennings.

It was resistance hidden in plain hearing, and it worked. Ordinary conversations became cover operations, and an ancient dialect briefly became one of the Allies’ most unassuming secret weapons.

From Shame to Pride

Ironically, after liberation in 1945, Jèrriais nearly disappeared. Schoolchildren were forbidden from using it, parents were told English was the “language of the future,” and native speakers were ridiculed for clinging to the past. By the 1980s, fewer than 500 fluent speakers remained.

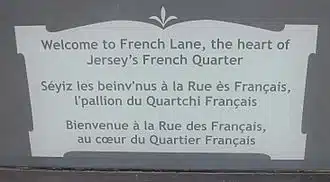

But the tide turned. In 1999, L’Office du Jèrriais was formed to keep the language alive. Children now learn it in schools, road signs appear in both English and Jèrriais, and musicians sing it proudly on stage. In 2019, the States of Jersey officially recognised it alongside English and French. Suddenly, the “peasant tongue” became a cultural badge of honour.

A Living Link to Identity

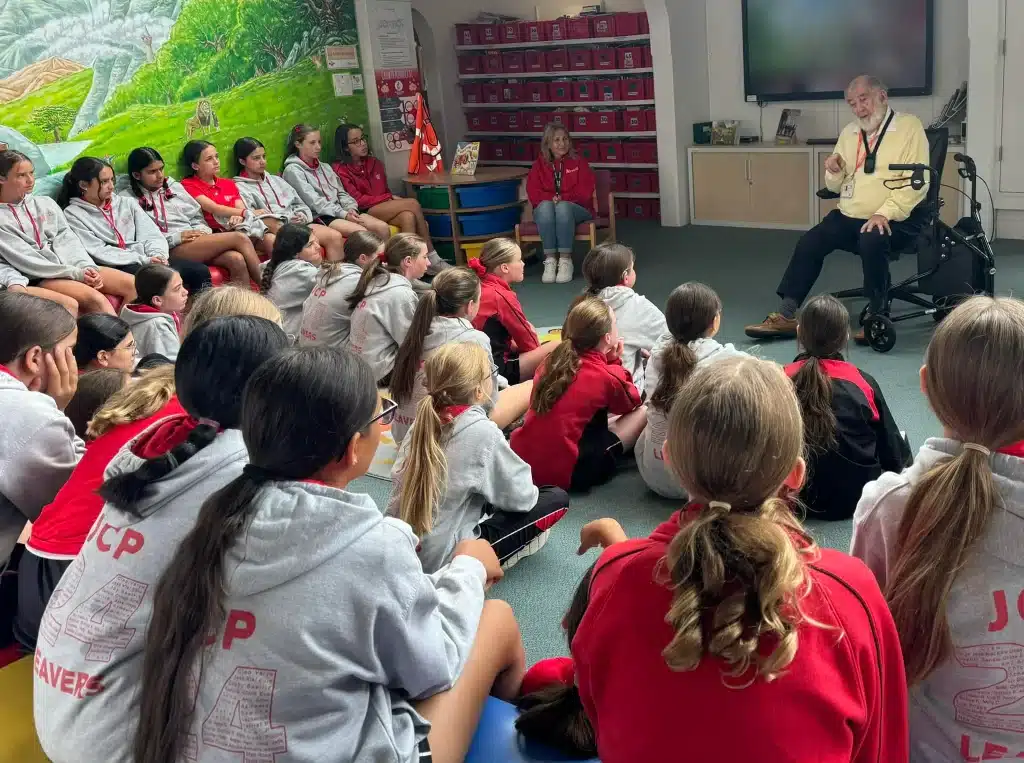

For people like 87-year-old Francois Le Maistre, who grew up speaking nothing but Jèrriais, the revival is personal. “Our language is so rich in words, phrases and expressions which simply don’t have any equivalent in English. If Jèrriais disappears, it’s not just words we’re losing. It’s much more than that. We’re losing part of who we are”.

From Nazi resistance code to endangered dialect to classroom subject, Jèrriais has travelled an extraordinary path. And while it may never again be a wartime secret weapon, it now serves as a proud symbol of cultural defiance—proof that sometimes, the sharpest sword in history isn’t steel, but speech.