The winter wind screamed across the Great Lakes, but for the men who marched out onto the thick ice, it was not just cold, it was profit. Imagine horses dragging heavy ploughs across a frozen lake to cut neat grids, while men with long saws bent over the ice to slice out perfect blocks. The air cut their lungs, beards froze stiff, and a single misstep meant plunging into deadly waters. Yet for nearly a century, this dangerous harvest created an extraordinary industry that kept food safe, medicines usable, and people alive long before refrigerators hummed in kitchens.

Turning Water into Wealth

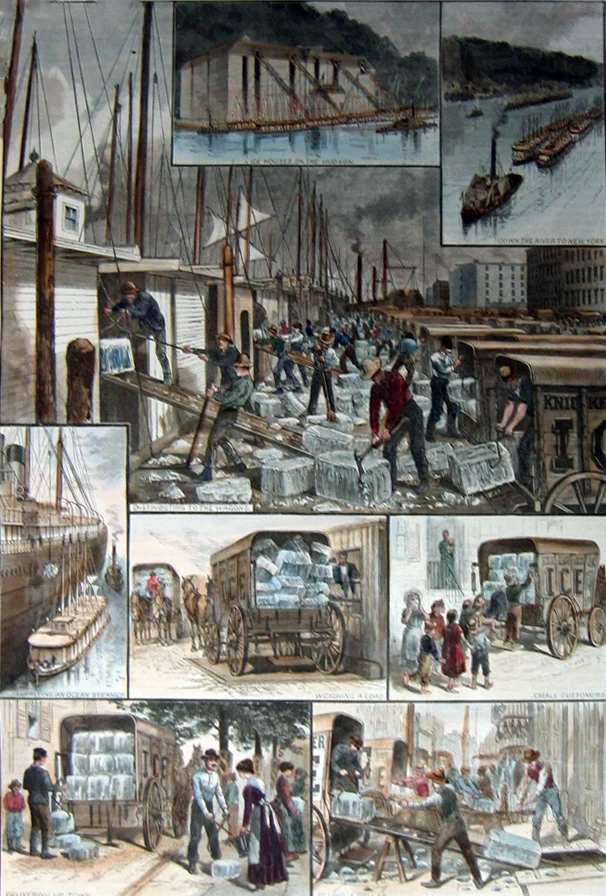

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States was hooked on ice. Before electricity and refrigeration, summer survival depended on the frozen harvest of winter. Cities from Chicago to Cleveland relied on clear blocks cut from Lake Michigan, Lake Erie, and countless smaller lakes across the Midwest.

To modern eyes, it may seem strange to treat frozen water like gold, but in an era when spoiled meat, rotten milk, and curdled cream were a constant threat, ice meant life and commerce. Men carved wealth straight out of nature, and people stored it carefully, knowing its value stretched beyond luxury into survival.

The Ice Harvesters’ Craft

The method was both simple and brilliant. Once lakes froze thick enough to hold men and horses, workers moved out in teams. Horses pulled special ploughs that scored the surface into neat checkerboard patterns.

Then men with saws and iron bars pried loose giant cubes of crystal-clear ice. Each block, often weighing 250 to 300 pounds, was floated along channels cut into the frozen surface before being hauled ashore. It was backbreaking labour, but with rhythm and skill, the blocks stacked high like shimmering bricks of a giant frozen wall.

On shore, massive ice houses waited. These giant warehouses, some the size of barns, were lined with insulating sawdust. The sawdust kept the blocks from melting and sticking together, and amazingly, the ice could last right through the summer.

From there, barges, trains, and wagons carried it to thirsty cities. A glass of lemonade chilled in July, a block of butter kept fresh, even medicine and vaccines in the early 20th century were kept viable thanks to the cold of these ice blocks. The frozen harvest formed a chain of survival from lake to city street.

A Dangerous Trade

The work was brutal and unforgiving. The ice was never fully predictable. Sometimes cracks split across the surface without warning. Men were crushed between sliding blocks or pitched suddenly into the freezing black water below.

Horses too could fall through, thrashing as men tried to haul them out. Fingers froze, limbs stiffened, and snow blinded workers as they pressed on. It was one of the hardest jobs of the era, and yet the men carried pride in their skill. They knew they were shaping survival.

Without them, summers in cities would be unbearable, food would spoil, and disease would spread faster.

An Industry That Disappeared

For decades, the frozen harvest was one of the most extraordinary feats of engineering and endurance. At its peak, the industry employed around 90,000 workers and carried an estimated capitalisation of 28 million dollars in late 19th-century America. But technology never stands still. With the arrival of mechanical refrigeration and eventually home refrigerators, the natural ice trade collapsed.

By the 1930s, safer refrigerants and widespread adoption of fridges pushed the ice trade into history. The once-mighty ice houses stood empty, their sawdust insulation left to rot. Barges that once carried shimmering cargo lay tied up and useless. What had been a vast, thriving industry melted away, leaving only stories and faded photographs.

Why It Matters Today

Looking back, the scale of the ice trade still amazes. It turned frozen lakes into a vital resource and linked cities through an invisible chain of cold storage. It also revealed human resilience, as workers braved conditions that tested the limits of body and spirit. While modern people take the hum of a fridge for granted, the extraordinary engineering of ice harvesting reminds us how far human ingenuity will go to turn nature’s most hostile moments into something life-saving.